Barnett’s 2003 speech

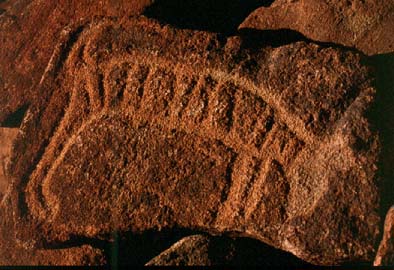

Petroglyph of a presumed thylacine, an extinct mammal, now itself to be destroyed by the state government of Western Australia in an act of state vandalism

|

Address to the National Trust of Australia (WA) on 7 April 2003

by The Hon. COLIN J. BARNETT, MLA

Leader of the Opposition (subsequently Premier of Western Australia)

BURRUP ROCK ART – Protecting heritage and sustaining development

All too often conservation and development are portrayed as opposites, however, that need not be the case. And while no one would deny that mistakes have been made in the past, these do not excuse mistakes made today.

The Burrup Peninsula is a classic case of competing conservation and development goals.

Iron-ore handling facilities, natural gas for domestic and export markets, evaporative salt fields and support services for off-shore petroleum exploration already form an industry base of national importance. The massive gas reserves now proven have the potential to establish the area as the most significant industrial complex in Australia over the next 30 years.

The ‘Burrup’ also happens to be the site of one of the world’s great heritage treasures. Put simply, it hosts the largest concentration of ancient rock art known.

The challenge is to protect this unique heritage while at the same time achieving the economic potential of our huge gas reserves — arguably Australia’s most valuable natural resource for this century.

It is not a matter of trading off one objective against the other, but rather of ‘thinking outside of the box’ and realising both economic development and heritage values.

ROCK ART

The Aboriginal rock art (or petroglyphs) on the Burrup are estimated to number about 300 000 across some 2000 sites. This is by far the largest concentration, or ‘gallery’, in the world. The rock art is ancient with most examples believed to be 6000 to 8000 years old. Some of the older examples are estimated at 10 000 years.

To give a perspective, this rock art is at least twice the age of the Egyptian pyramids and is clearly of world significance.

The carvings have been made in weathered rock by a percussion action that has exposed the lighter colour rock below the surface. About half of the carvings are schematic shapes and patterns. Human and animal motifs are common including turtles, fish, birds, emus and kangaroos.

Although noted by explorers around the mid-19th century, the region’s rock art remained largely unknown until the 1960s. The first study was conducted by the WA Museum in 1964 [at nearby Depuch Island] in response to the initial industrial development in the area.

The area includes other ancient man-made features including ‘standing’ stones and walled structures. Little is known or understood about these.

INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT

As well as this rich natural history, the Pilbara also has a fabulous natural resource endowment. The region is the location of one of the two great iron-ore provinces of the world. The first development of this resource was the Mt Tom Price mine with associated port, rail and township facilities at Dampier. A causeway was constructed which converted Dampier Island into what is now known as the Burrup Peninsula.

The first iron-ore exports by Hamersley Iron took place in 1966. The Dampier solar salt fields were also commenced in the late 1960s.

Natural gas was discovered in offshore waters in 1971. The development of the subsequent North West Shelf Project saw domestic gas supplies to Perth and the south-west from 1984 with the first LNG exports in 1989.

The construction of these huge projects inevitably resulted in the loss of a significant number of rock art sites. It is estimated that around 20-25% of all petroglyphs were destroyed. From the site of the gas facilities, some 2000 engraved boulders were removed and placed in ‘temporary storage’, where they remain today.

What is done is done. The point is that with today’s understanding of the importance of this heritage there is a clear responsibility to make the right decisions for the future.

BURRUP MANAGEMENT PLAN

The re-structuring of long-term gas supply contracts in 1995 brought about an immediate deregulation of gas prices in the Pilbara. The price of natural gas for prospective major projects fell by about half to a value well below that of North America and Europe. The political stability of Australia coupled with the rapid market growth for chemicals in Asia sparked an immediate interest in gas processing projects.

At the same time a consortium of Dowell-Shell was studying the potential for a world-scale petrochemical plant based on the increasing supply of ethane associated with rising gas production.

The problem was where to locate these potential investments. A problem compounded by the lack of infrastructure (i.e. power, water, transport) and the economic imperative to achieve a synergy of the plants being co-located to facilitate ‘over the fence’ trade and cost sharing on common services.

The Burrup Peninsula Land Use Plan and Management Strategy (1996) was an attempt to balance industry, conservation and heritage needs.

More than half (62%) of the Peninsula was set aside for conservation, heritage and recreation uses. Five areas were identified for industrial use, including the existing industrial leases. The government of the day subsequently ruled out the most northerly of the industry sites (Conzinc South) on the basis that industry should not extend to the north of Withnell Bay.

That left the total of existing and prospective industry sites at just 1,630 hectares. The largest prospective area and the only flat (tidal) area for future development was Hearson Cove.

Land was allocated for three prospective projects in Hearson Cove (Plenty River, now Dampier Nitrogen, Burrup Fertilisers; and Syntroleum.). In 1999 a state government commitment of $30m to support the establishment of common-user infrastructure (water supply, port upgrade, service corridor and road works) on a user-pays basis was announced.

There would remain the potential for perhaps another 2 to 3 medium sized projects in Hearson Cove. Thereafter the area would have achieved capacity.

In the meantime it had become obvious that there was no area large enough to accommodate an integrated petrochemical complex. West Intercourse Island was examined as an option, though this area was rich in rock art presenting the same problems of past developments.

It was from these constraints on industrial development that planning began for a ‘greenfields’ industrial site to the south of the Burrup Peninsula.

MAITLAND INDUSTRIAL ESTATE

Hearson Cove could only ever be a small-scale industry site to accommodate immediate projects. Neither it nor any other site on the Burrup could physically accommodate the full potential of a world-scale chemicals complex.

The development of the Maitland site to the south was always an economic imperative. Preliminary planning in the late 1990s designated a large and flat area of about 4000 hectares at Maitland with the appropriate zoning and infrastructure plans in place. The Maitland estate would be connected by a transport corridor to future shipping facilities off West Intercourse Island.

The ultimate development of Maitland would be expensive with estimates of about $300 million. Development would, however, be staged and carried out concurrently with the construction of industrial projects. The $300 million figure also should be considered in the context of the current government’s promises of $134 million to support what can only ever be a restricted development on the Burrup itself.

IMPACT OF INDUSTRIAL EMISSIONS

Airborne emissions are an inevitable consequence of heavy industry. The existing projects on the Burrup produce mainly carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from power generation and as a waste component of natural gas reservoirs. These greenhouse gases, while of global significance, pose no direct threat to the rock art.

Gas processing plants may well be a different story. The process of chemical change gives rise to a wider ‘cocktail’ of emissions. The production of nitric and sulphur oxides creates the basis of an ‘acid rain’ effect.

Somewhat ironically, the potential danger may be exacerbated by the arid climate with atmospheric deposits building up on rock surfaces only to turn acidic when moisture is present.

There is a genuine concern within the scientific community that such a process may erase the rock art within a comparatively short period. The point is, we simply do not know.

The current government has established a Burrup Rock Art Monitoring Committee to conduct a four-year study. However, it is problematic if the answer can be found in that time period when the preliminary task of properly recording the rock art has not even been done.

THE WAY FORWARD

Not surprisingly, the Burrup rock art is rapidly gaining international attention. In some quarters, there are already calls for a world heritage listing. Until the land-use issues are properly resolved, such a listing would be premature. However, this potential status will inevitably be a factor in ‘due diligence’ for project finance.

At a local level, the tourist potential of such an ancient and unique site is only now being recognised.

The way forward is to ensure the protection and integrity of the rock art. Any further physical disturbance should be kept to a minimum as should the threat of chemical deterioration. The landscape setting is essential to the overall amenity of the area in order that future generations can also experience and discover for themselves this ancient heritage.

For industry, a bold step is required. Some industry can be accommodated at Hearson Cove. Thereafter future projects will need to be at a modified Maitland Estate.

For this to occur the planning and development of Maitland must be re-started as a matter of priority.

Even current proposals should be offered, without duress, a Maitland alternative. The prospect of lower construction costs, greater security for finance providers and savings through a more widely shared infrastructure and utilities may well prove attractive.

Failure to act boldly may see further examples of valued projects being either abandoned or delayed.

This is not a case of finding an uneasy compromise, but rather of seeing the bigger picture and grasping the opportunities presented by the coincidence of Australia’s most significant heritage site and a fabulous wealth of natural resources.